I’m a Psychiatrist and Here’s What I Want People to Know About My Suicidal Ideation

Honestly, it’s OK to ask me about it.

Content warning: This piece contains descriptions of suicidal ideation and suicidality. If you or someone you know is in crisis, please contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988.

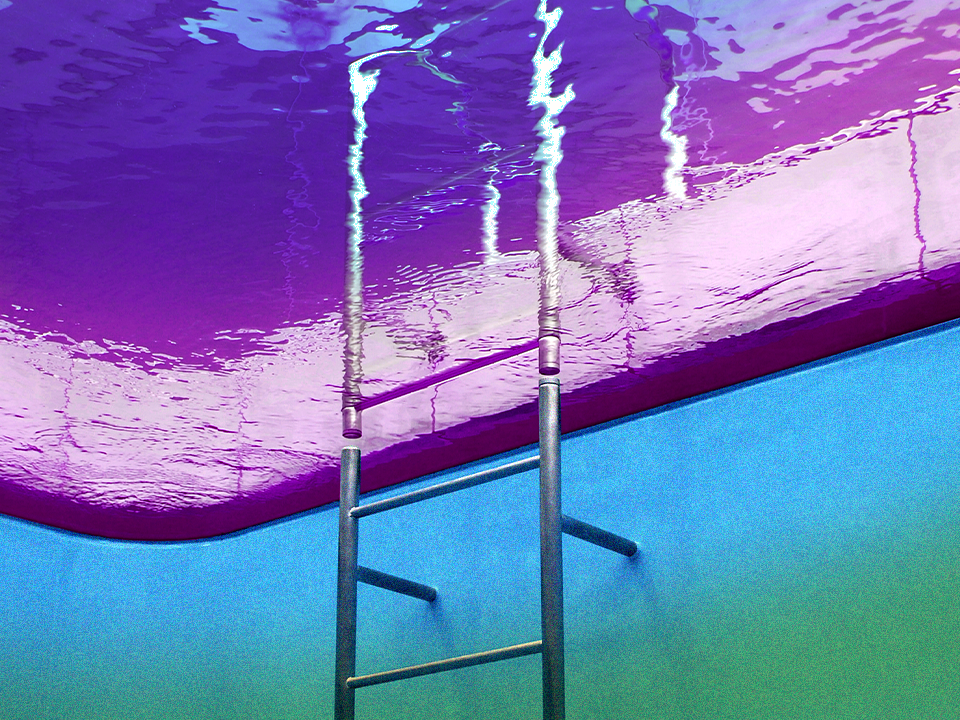

A single thought ran over and over and over in my mind as I tried to remain standing in the shower.

Today is the day I kill myself.

The steaming water from the showerhead didn’t warm my body or mind gripped by panic and suicidal ideation. I was in survival mode. Tears streamed down my face, and I felt embarrassed by my weakness. My lips trembled. I couldn’t allow myself to vocalize the screaming inside.

When my knees started to buckle, I sat in the shower. I held them tight to my chest and continued to sob. The crushing weight of racism, homophobia, and prejudice had led to this moment, and I couldn’t stand my mind incessantly playing each instance of discrimination anymore. I held my legs closer; a Black, gay, second-year psychiatry resident training at a prominent hospital. I felt utterly alone as I planned to end my life.

I knew that if I stepped out of the shower, I would act on these thoughts. Yet, an internal force kept me in place. It told me that it was OK to stay seated, to slow down for a second. Like so many times before, my subconscious sprung into action and dug up happy memories of spending time with the chosen family my friends became in college and graduate school. I tried to remember how to breathe deeply as I thought about my mom, dad, and sister, and how I wanted to hold them in my arms and tell them I loved them.

After 20 minutes, which felt like hours, I left the shower. My suicidal thoughts were still present, but the intent was in remission. I wiped the corners of my eyes and started getting ready for the day, hoping that things would get better and that I’d never go through such a period again.

It’s been four years since that morning, and I feel whole and happy in a way I wasn’t sure would ever be possible.

But suicidal ideation (having suicidal thoughts) doesn’t always go away. I still sometimes deal with suicidality (which refers to the risk of suicide indicated by suicidal thoughts or intent), particularly when I experience—or see others experiencing—harassment, minority stress, or discrimination.

Suicidal ideation is more common than most people think.

In 2020, roughly 1 in 9 young adults had serious thoughts of suicide, according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Unfortunately, the shame around these thoughts can keep people from talking about it or reaching out for help when they need it most.

That overwhelmingly stems from living in a society that stigmatizes people with mental illness, according to the American Association of Suicidology. When it comes to suicidal ideation, negative portrayals of mental illness in the media certainly aren’t helping. Neither are people who dismiss or distance themselves from anyone who shares their experience with suicidal thoughts, not to mention health care providers who treat patients’ physical issues after an attempt but fail to address the mental health issues that led to self-harm in the first place.

Four years ago, even as a psychiatry resident at a Boston hospital, there was no way I could say, “This morning I didn’t want to be alive anymore,” but today I know just how important it is to talk about my experience. I saw how opening up to my friends and family (and the internet) normalized this part of my mental health and bonded us through compassion. Their care and openness created magic, making me feel safe, seen, and heard.

My hope is that people living with suicidal ideation, who might sit in the shower in the morning contemplating ending their life, realize that they aren’t alone. I also hope that those who care about them—or even just know them—take the time to understand that experience and become a source of support when things get tough.

With that in mind, here’s what I want people to know about suicidal ideation.

1. Suicidal ideation can be a symptom of a problem that you want solved.

When I’m suicidal, it means there’s disharmony within myself, my environment, or both, and I have to figure out the reasons for that discord. Like I mentioned earlier, those reasons often center around feeling trapped and powerless. I’m now at a point—and have been for years—where I know how to break down the overwhelm I feel into smaller, solvable problems, which often helps me abate those hopeless feelings.

And that’s how I describe suicidality to the kids, adolescents, and young adults I work with: There’s a problem they don’t know how to solve, and their suicidality has arisen as an end-game solution.

That idea helps decrease any internalized shame they might feel and normalizes the fact that suicidality happens—because it does! Then, we can work on figuring out what their problems are and find solutions other than suicide.

2. Talking about suicidal ideation won’t cause suicidal thoughts or actions.

One fear many people have is that asking about suicidality may induce suicidal thoughts in someone who previously didn’t have suicidal ideation. But research suggests that’s not the case.

In a review of research published in 2014, researchers found that there was no statistically significant increase in suicidal ideation among participants who were asked about suicidal thoughts. In fact, they wrote that acknowledging and asking about suicidality may reduce suicidal ideation and lead to improvements in mental health in treatment-seeking populations. Those findings have been replicated over the years, suggesting that talking about suicidality with those you’re close to can provide space for vital conversations for people living with suicidal ideation.

3. Suicidal ideation can be hard to spot.

Believe me, when someone is living with suicidality, it takes strength for them to share openly that they live with thoughts of killing themselves. I live with a history of two suicide attempts, one in high school and one in college. No one knew about them, and no one found out until I began speaking openly about my history of mental illness.

And I’ve found that people still can’t tell when I’m experiencing suicidal thoughts. Even if they can see that I might be in the midst of a depressive episode, it’s probably impossible to tell if I’m thinking about suicide. Part of that is likely because, as a Black, gay, non-binary person in America, I’ve often been forced to mask my symptoms in order to present an image as a “perfect minoritized person” to the world.

Because it’s hard to see when someone is dealing with this, you never know who could be hurt when people say things like, “Dying by suicide is weak or selfish or taking the easy way out.” As a psychiatrist, I know how to handle those comments, but words like this could stop someone else from getting life-saving care.

4. It’s OK to ask me about it.

My suicidal ideation is just one sliver of who I am as a person, so I don’t want that to be the only thing my friends and family talk to me about—especially if I’m doing well right now. That said, it actually makes me feel seen when someone who knows about my history cares enough to ask how I’m doing internally. I appreciate those questions and see them as evidence that I matter.

But this isn’t the case for everyone living with suicidality. Because some might understandably feel a little uncomfortable talking about these kinds of thoughts (you know, given ALL of the stigma), think through what’s making you want to ask them about it before you bring it up.

For example, have they recently gone through a traumatic event? Have you noticed a change in their mood or behavior? Did they send you a message recently that seemed out of character for them?

Coming into the conversation with those things in mind enables you to open the floor for them to talk about what they’re feeling. You can try, “Hey, so I’ve noticed that you’re more X than before, and I was wondering if something was going on,” or “I’ve noticed X lately and wanted to talk about it with you, if you have time.” From there, the conversation can naturally progress to asking them directly if they’re experiencing suicidality.

5. Suicidal ideation isn’t caused by just one thing.

People often incorrectly assume that there’s one reason why a person might have thoughts of ending their life, which reduces an extremely complicated issue down to one source and does a disservice to the issue of suicidality as a whole and people struggling with it.

In reality, suicidality and its causes are unique to everyone dealing with it and often involve both genetic and environmental elements. Those risk factors could include mental health conditions like depression and bipolar disorder or prolonged stress caused by harassment, bullying, or financial issues. A history of trauma or family history of suicide can also contribute to suicidal ideation.

My suicidal ideation arises mainly because of minority stress, a concept described by Ilan Meyer, PhD, in which minoritized people experience stigma, prejudice, and discrimination unique to those populations that create hostile and stressful social environments leading to mental health problems. I also have a genetic predisposition, however, I didn’t begin to experience depression or suicidality until I experienced both overt and subversive discrimination for being gay in 7th grade. When I feel safe and am not experiencing daily prejudice, my suicidality and depression subside.

6. Everyday moments of kindness and companionship have saved me.

When my suicidality went from passive to active (meaning there's some level of intent or planning in your suicidal thoughts), every memory of positive interactions helped me keep going. When I woke up screaming from nightmares about discriminatory events and felt suicidal, I calmed myself by remembering the funny gif a friend sent that day. When I sat alone in my apartment crying, thinking about my group chats or dinners with close friends where I feel accepted and loved for being their Black, gay, unicorn phoenix reminded me that I wasn’t truly alone.

In 2022, The Trevor Project found that 45% of LGBTQ+ youth surveyed seriously considered attempting suicide in the past year, and nearly 1 in 5 transgender and nonbinary youth attempted suicide. Not only that, but LGBTQ+ youth of color reported higher rates of attempted suicide compared to their peers. But that same survey also found that LGBTQ+ youth who live in a community that welcomes them reported attempting suicide at a rate less than half of those who felt low or moderate social support.

This is just one example of how connectedness and community (along with problem-solving skills and mental health care) can help people who experience suicidal ideation heal.

7. We can live full lives.

Back in medical school, I remember when a few classmates said that someone living with suicidality couldn’t have a full and meaningful life. But their comments were based on a lack of understanding.

People like me can and do live lives that mean a great deal to them and to those around them. We are your teachers, your doctors, your favorite sports figures, your beloved actors, your friends, and your family members. Just because we have some added complexity to our mental health, it doesn’t mean that we don’t want and deserve the same things as everyone else.

I remember speaking up that day, but I didn't feel safe enough to share my experience. If I did, I would have said that I was facing depression fueled by discrimination at that moment, and yet I was living a full life. Four years after that morning in the shower, I still am.

I’m now an assistant professor in child and adolescent psychiatry at the University of California San Francisco. I’ve recently returned to Boston for a conference on mental health for minoritized people, and I will be presenting at the same university where four years ago I was sure I would die. The conference begins tomorrow, but I returned early to see my chosen family who saved my life over and over through sheer force of presence. I’ve returned more confident, more openly myself, and glad to be alive.

Wondermind does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Any information published on this website or by this brand is not intended as a replacement for medical advice. Always consult a qualified health or mental health professional with any questions or concerns about your mental health.