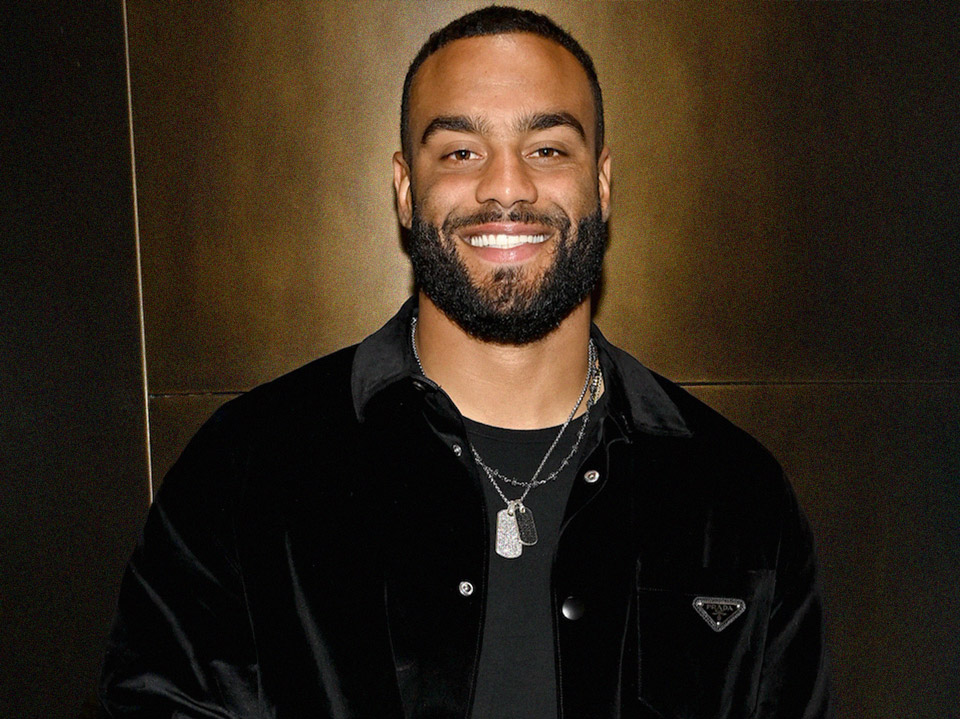

Solomon Thomas Is Talking About His Feelings in the Locker Room

The NFL defensive lineman knows how important—and how brave—it is to be vulnerable.

Solomon Thomas was about seven weeks into the NFL season last year when he started making sourdough bread. “I wasn't playing well, I wasn't feeling good mentally. And I was like, I need to do something. I need to break the routine of going home and just thinking about football.” Pretty soon he was making a few loaves a week for his teammates, and some of the other New York Jets players got in on the action too. “I know it doesn’t sound like a mental health thing, but it was so therapeutic for me to have a hobby outside of football to go home to.”

Baking bread is hardly the only tool in Thomas’s mental fitness toolkit. The defensive lineman tells Wondermind his mental health routine involves therapy, meditation, journaling, exercising, getting outside, and plenty of deep conversations with friends.

Thomas never expected to be a mental health advocate and co-founder of a mental health foundation. Then, six years ago, he lost his sister Ella to suicide, and everything changed. Out of unthinkable heartache, The Defensive Line was born. “Our mission is to end the epidemic of youth suicide, especially for young people of color, by transforming the way we connect and communicate over mental health,” says Thomas, who was recently awarded the 2023 Heisman Humanitarian Award.

The foundation, which he co-founded with his parents, brings suicide prevention programs into schools, businesses, and collegiate sports programs to better equip anyone in a mentorship role (teachers, coaches, etc.) to spot the warning signs, respond in a crisis, and create a safe space to share what’s going on. “When I was growing up in school, by the time I got home, I wasn't going to talk to [my parents] about my feelings. The people who were going to see my changes in behavior were my teachers, my coaches. And it's the same thing at work,” says Thomas. “Just trying to train everyone to understand mental health and the warning signs and the questions—I think that's a huge part of suicide prevention and mental health awareness.”

Here, Thomas shares more about his mental health journey, how he keeps Ella’s memory alive, and his strategy for getting more guys to talk about their feelings in the locker room.

WM: How are you, really?

ST: I am good right now, but at the same time—ever since the season ended on January 8th—I've been living in a very anxious state because I'm a free agent this year. So that means in March, I don't have a team. I don't technically have a job yet. And so I pack up my place in New Jersey, I put it all in storage, and I go live with my parents as a 28-year-old. I go train at home and I just kind of wait to see what's next.

And I'm a homebody. Home, for me, is peace. So not having a home right now is hard. I've been home probably four to six days in February, and I've been traveling on the road doing a lot of things. So today's been a good day, but definitely each day has been a little bit of a different struggle being in this space of the unknown and not knowing what's next. And I'm just really excited to figure out where I'm going to be playing next, where I'm going to be living. I am good, but I'm also figuring out this anxious state that I'm looking at.

WM: What are some ways that you deal with that uncertainty?

ST: I'm really thankful that I've been in this work the last few years. Now I have things to rely on to deal with my anxiety and to deal with this state of uncertainty so I'm not stuck in this state of being on edge all day. I can journal. I think it helps me out a lot, helps me stay grounded. I'm a big overthinker, so it gets my thoughts out of my head.

Also I have more time now that we're not in season, so I'm meeting with my therapist a lot more. We're probably meeting one to two times a week, and she's been amazing and really helping me to just get back in the flow of life and understand, hey, we're in this state right now, but you can still function in this state and you can still have good days in the state.

And, past that, training is a big part of my job, but it also helps me out mentally a lot when I work out. I love training, I love being in the gym. It's kind of like a peace for me. But also getting outside, getting a lot of sun. In season, we go through a lot of pain and trauma, so getting my basic vitals in—whether it’s vitamins, going on walks in the sun, listening to certain music—helps me be more calm.

And then just having these conversations with my friends and talking about it. Last night I called a friend and we had a conversation about, “Hey, we know it's about to come up. We know it's about to be stressful and anxious, but I got your back. We can get through it. Good things are coming our way.” It’s positive affirmations we're telling each other, but also just like, “Hey, we're not alone. We've been through this before together, and we're going to get through it together again.”

WM: Can you tell us about your mental health journey? Is this something you’ve always been passionate about?

ST: I really never thought I would be here. I was always sensitive growing up, very emotional. My parents raised us to know our emotions, to love and to be there for each other, and to communicate these things. But, at the same time, being a young man growing up in a locker room a lot and being in competitive sports, it was something that I never really did. … So mental health was never a big thing for me or something that I really believed in growing up, but it became a huge passion of mine.

In 2018, I lost my sister to suicide, and my family and I were thrown into this mental health world, and it was just a world we knew nothing about. Ella died by suicide, but people never talked about it. They would talk about Ella dying and Ella not being here, but it was never: “Why isn’t Ella here? What signs did we miss? Did you know this about Ella?” It was just something we didn't talk about, and it kind of threw me and my family into this very empty world where we felt alone. We felt like we couldn't talk about it. We felt like people weren't there for us. People were there for us—we had the most amazing support in the world—but around the subject of mental health, we didn't feel like people were there for us so we could have that conversation.

There's no right way to handle that type of death, but I didn't handle it correctly. I kind of suppressed my emotions. I was told: Be strong for your parents, give it to God, pray about it and you'll be fine. In my head, I'm like, OK, people go through this all the time. People lose people. I'm going to be OK. And I kept trying to move on that way. I'd lost loved ones before, but my sister was my person. She was my constant in this world of moving around all the time. She was a person who made me feel like I wasn't weird. She made me feel normal, and she made me feel validated. And not having her here, it was a new feeling and sensation of being alone and being empty.

So I would suppress these emotions, and then my world just kept getting darker and darker. And it got to a point where the season had started and I had just gotten a concussion and I was alone a lot. You have to sit in a dark room after concussion. And I started getting these deep, dark thoughts—thoughts I never thought I would have before. And I kept judging myself for these thoughts. Then you get in this pattern of not wanting to wake up, not wanting to go to sleep, and I'm stuck in suicidal ideation—not even knowing what that meant at the time—and just in a really hard place.

One morning before work, my general manager, John Lynch, came up to me and he was like, hey, so we know you're struggling and we got your back, and if you need help, we got you. At this time, I had been refusing to go to therapy. … I had seen a sports psychologist [when I was at Stanford University] for a little bit. And I went back to her for one session and she asked me that question—she said, “How are you doing, really?” And I just started bawling, crying in the session and talking about Ella and how much I missed her and how much I'm struggling. And at the end of the session, she told me, “Hey, Solomon, you need to get better help than me. I'm not cut out for what you're going through.” After that, I was like, That's my sign. Therapy's not for me. If she can't handle me, who can? And then, going back to John, that conversation lifted the weight off my shoulders. And after that, I was finally able to get help.

From going to therapy, I learned how to understand my depression, understand my sadness, to talk about it, to put it into words. She taught me how to have coping mechanisms when these things come up. She taught me that it's OK to cry. It's OK to feel this. You don't have to feel good right now. You're not supposed to feel good right now. You're learning how to live again.

So my philosophy and my family's philosophy is: If doing this work, having these talks, putting my vulnerability and my deep dark secrets out there—which is something I never thought I'd be doing—if that saves one life, if that saves one person from going through the pain that Ella went through, or if that saves one family from going through the pain that we go through for missing Ella, it's all worth it.

Of course, the one thing I would change about this whole journey is Ella being here. I want her here more than anything. But going through this journey, I've learned a new way to live, a new way to connect with people, a new way to see life. And I wouldn't change that, because we get this one life and I want to feel it, and I want to help people, and I want to be here and make a difference. And I think this is my way, and this has been my calling.

WM: As you mentioned, feelings probably don’t come up in the locker room often. What advice would you give to men who are still apprehensive about discussing their mental health or seeking professional help?

ST: First of all, I would like to say in the locker room we have started to talk about it! We have a corner in the Jets locker room—it's an older vet group, guys that know my story—and we'll talk about therapy. And sometimes the younger guys come around and they'll start listening. So [we’re doing our best] to change the status quo of locker room talk.

But, to answer the question, for men, I just try to tell 'em: Hey, there's no shame in talking about your feelings. There's no weakness in being vulnerable. There's no weakness in being sensitive or being able to feel. We always talk about being strong, tough men and being masculine, and we want all those things. If you just go through your day and tell someone you're fine all day—that's easy. That's not strength. But how hard is it for a man to go to someone and tell them how they're feeling? That is strength, that is real vulnerability. That is real power. So I try to tell guys, if you want to be that strong man, you talk about these things. We have these hard conversations.

Part of being the man that guys talk about all the time is being the best. And if you want to be your best self, you have to know yourself the best. And the best way that I know how to do that is through therapy. You learn: Why do I like these things? Why do I feel these things? How do I put it into words, how do I talk about these things? You get to know yourself so well.

Another thing that I tell guys is, from an athlete perspective, when I was going through that dark time in San Francisco after my sister died, I wasn't playing well. I didn't really care about playing. I was still giving my all, but things weren't working out. Then I started going to therapy, started getting help, and my mind cleared up. And when that did, I started playing better. My body was moving faster, more explosive, stronger. If you know anything about the NFL season, it's really treacherous. It's really hard. There's no way you can get bigger, faster, stronger during the season. But by just clearing my mind and clearing my mental health, I was able to do that.

WM: In the years since your sister’s passing, what have you learned about grief and how to navigate it?

ST: Grief is such an interesting, weird, and crazy thing. I like to describe it like I have this hole in my heart and it's never going to go away. My mom always says grief is like a wave. You ride the wave for a little bit, then it crashes again, and then you ride it for a little bit, then it crashes again. You don't get to control grief. It will come and hit you in phases at any time. You never know what's going to hit you.

I carry my sister's death with me a lot better now, six years later, but there's days that it hurts like it’s day one all over again. I used to run from these feelings of sadness, depression, anger around her death, the anger of missing her, the guilt around missing her, the guilt around learning what to do later and all this stuff. But I learned when I ran from that, I let Ella actually die, and that killed me. But when I accepted those feelings and I felt them, I was able to connect with her. I was able to see what she went through and learn her journey and learn more about her—even though she's not even here anymore. And that, to me, was the most powerful thing. I was able to feel her still be here. I was able to keep her spirit alive.

When I cry, I feel like I'm honoring her. I feel like I'm letting her know, “Hey, I miss you and I want you here.” Or when I'm angry about it, I'm just letting her know, “Hey, I'm just frustrated. You're not here, but I'm going to keep living for you.”

I don't know if I call it a coping mechanism, but accepting these feelings is huge for my grief journey and keeping Ella alive with me.

WM: What is one aspect of your mental health that still feels like a work in progress?

ST: I would say consistency, but also I would say self-talk. I'm very proud of how much my self-talk has gotten better, but it's still a theme in therapy. My therapist reminds me all the time, “Hey, why are you judging yourself right now? Why are you judging 8-year-old Solomon? And I'm like, dang, I really am. I need to be nicer to myself.

I think it's something we all do—especially people who are in high-performance and high-competitive lifestyles. We're very hard on ourselves. I can be hard on myself and push myself, but I can also love myself through it. So working on that and not judging myself is something that I'm definitely working on hard right now.

WM: Speaking of 8-year-old Solomon, what advice do you wish you could go back and give your younger self?

ST: I think the biggest thing that I should have told my 8-year-old self is to love myself unconditionally. I don't believe I really loved myself until two years ago. I’ve made this habit: the first thing I write in my journal, no matter what I'm writing, is: I love myself unconditionally. Because I went through such a hard time of judging myself, not loving my appearance, whether it’s body dysmorphia, not liking the way I look, not liking the way I make friends or how I feel alone and weird.

So just to love myself unconditionally and to be authentically and unapologetically Solomon Thomas, however that comes. There's one me, and I'm unique and great in my own way, and I should love that about myself. I feel like that would have helped me out a lot when I was younger, whether it was moving around and feeling like I couldn't make friends or feeling weird and awkward, but also to understand that weirdness and awkwardness that I'm feeling makes me who I am and to love that about myself.

WM: The NFL has been focusing a lot more on mental health recently. As someone in the mental health advocacy space, what do you think they’re doing right, and what would you like them to do more of?

ST: I'm very proud of the NFL. Three or four years ago, they put out an NFL initiative where they put more funding into making sure players can get therapy, that their family members can get help, and that there are more resources and clinicians available. I'm very proud of them for that. And also, this past year, they've been picking up more of The Defensive Line’s work and other foundations, like Dak Prescott’s foundation, Faith Fight Finish. And for the Super Bowl commercials, there was a big mental health push in those as well. So I'm very thankful for that. But I do think the NFL definitely does need to do a better job in a lot of ways. And the first way I'll say is educating these coaches and the GMs [general managers] and the guys who are making the decisions.

A lot of us now are getting more in tune with our mental health and accepting it, but a lot of the people who are not OK with it are the people who are supposed to be the mentors, the heads of the building making decisions. And I do feel like that plays a role in decision making or small things throughout the season. And I feel that has guys being reluctant to ask for help or to go to the clinician. And I think that's a mentality that needs to change. The coaches, GMs, player personnel owners need to be educated a lot more and understand that, hey, we're human beings. I know this is a business, but also you need to care about us in that aspect too. If I'm the owner, if I'm a GM, if I want my team to be the best, I want them to be the best human beings and people, because, like I said, this mental health/physical health connection makes you the best athlete possible.

Past that, I don't think enough is done [for guys after they’re done playing]. The game of football—we all know, it's no secret—it affects our brain and it affects our brain health. And then that affects our mental health and how we act. There needs to be more education and push for players when they're done playing to make sure they stay on top of their blood work and vitals to see how their chemistry is changing. There needs to be more funding for guys to get therapy and get these mental health resources after they're done playing.

Because when we're done playing, life's going to get a lot harder, or we're going to have identity issues, we're going to not know what to do. We might have financial issues, physical issues, all these things. And this is when we need the mental health help the most, because we lose way too many players. It's been really unfortunate. We lose way too many players when they're done playing to these issues—you could call it whatever you want, you could call at CTE [chronic traumatic encephalopathy], you could call it lifestyle choices, but it all stems down to taking care of your mental health. And it's a big problem. I'm proud of the league, but there is a long way we need to go, and I'm going to do my best to make sure I help the league in any way I can.

WM: What else would you like to share with our readers who might be going through a hard time right now?

ST: It may seem super dark, but there is a small light of hope in the dark storm you're going through. And I would say to hold onto that light, to love yourself through it, to know that you're not alone. You're not crazy for feeling the way you're feeling. Honor your feelings, honor your emotions, you’re feeling them for a reason, and you're not crazy for feeling them.

Just understand that it’s OK not to be OK. It's OK to feel the way you're feeling. You're not going to feel this forever. Things will get better. You are loved and you're needed to stay here on this Earth. I always like ending with that, because there are too many people out there who are feeling those things right now and who feel like the only way out is to leave. And we need them to stay, because Earth needs them here.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Wondermind does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Any information published on this website or by this brand is not intended as a replacement for medical advice. Always consult a qualified health or mental health professional with any questions or concerns about your mental health.