I Got Diagnosed With Adult ADHD, and Now My Entire Life Makes Sense

“This is my cross to bear and my special sauce.”

Last summer while cleaning out my storage unit, I found an essay I wrote when I was 7:

I don’t think I am so good at turning in my homework on time. Sometimes I get confused and am going to miss my bus, so I rush out the door forgetting it. … I try to do my best to bring it in on time, but I just can’t do it. It is one of the goals I am going to work on, and I am still going to do my best.

I don’t remember writing these words, but reading them kind of broke my heart. I felt sad for this girl, so eager to please and optimistic about the possibility of change. So unaware of the hundreds of all-nighters that await her in high school, in college, and in her career as a magazine editor; of the panic attacks and self-recrimination, the harsh cycles of caffeine-induced hyper-focus and existentially empty comedown. This girl was unprepared for the constant overwhelm that would strain her future marriage and mental health (and do strain her marriage and mental health). Because this girl has been trying and failing to “bring it in on time” since the late ’80s.

And now, at 43, I finally know why. My journey to an attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) diagnosis began—as I’ve read it often does for women my age—with my 11-year-old son’s diagnosis. Only then did I actually begin reading about ADHD, a condition I’d never taken seriously despite a longtime understanding that I require uppers to do almost anything. Wasn’t ADHD mostly an excuse for helicopter parents to pump their kids full of meds? And aren’t we all kind of tech-addled and chaotic in the brain these days anyway?

But the literature blew my distracted mind. Things I’d chalked up to my religious upbringing, my air sign, or my lack of willpower were suddenly just symptoms or characteristics associated with ADHD: A tendency to blurt out personal things way too fast. A pathological inability to open mail or pay taxes. A weird mix of procrastination and perfectionism. A terminal boredom with normal life, which has manifested in an avoidance of the suburbs and (lately) full-time employment. My whole personality was right there in ADHD 2.0 by Edward M. Hallowell, MD, and John J. Ratey, MD. I had always considered my brain to be kind of original. Turns out the word I was looking for was “neurodivergent.”

(Yes, I know plenty of people with ADHD live happily in the suburbs and pay their taxes. But for me, the impulsivity and inattention symptoms underlying ADHD manifest in this particular minefield of traits.).

I cried three times during my expensive Zoom psychiatrist appointment. As the mustachioed doctor on my screen asked me detailed questions about my childhood and how often I forget things or finish other people’s sentences (“My husband’s, mostly”), I saw the dots of a hundred painful or shameful feelings and experiences connect so clearly.

I actually felt dumb and furious for not dealing with this sooner. Instead, I’d spent decades beating myself up, overcompensating, paying IRS late fees, and wrecking my health to meet deadlines. “Everything is just harder for you,” said the doctor, with compassion, before signing off. I was blubbering by then, waves of catharsis washing over me. He would send the prescription to my phone.

It was seductive to think I finally had an answer. That my life’s intractable challenges—productivity, emotional regulation, people-pleasing—were not defects of character but signs of a highly heritable mental condition. I wasn’t flakey, thoughtless, or careless; I had a legal disability. A diagnosis that’s associated with job instability, low self-esteem, substance abuse, and sleep problems, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). One that some research has linked to differences in dopamine activity in the brain.

So why could I still not shake the deep-down suspicion that the whole thing was a modern affectation more than an actual disorder? It didn’t help that my husband kept declaring, with each new symptom I discovered, that he also had it. In fact, in their book, Drs. Hallowell and Ratey write that many people without diagnosable ADHD have similar symptoms thanks to the “massive increase in stimuli that now bombard our brains and our world.”

In other words, you’re not wrong for feeling like everyone you know is suddenly slinging this acronym around. But the diagnosable condition always shows up in childhood; involves six or more attention or impulsivity symptoms; and interferes with “social, academic, or occupational functioning.” It’s also famously underdiagnosed in girls, who, studies show, may be better at masking our symptoms (probably because we’re judged more harshly when we don’t).

I checked all the boxes. And yet it was hard to release decades of conditioning that screamed I was the problem. I hold that shame deep in my core, the underside of my stubborn optimism, which still had me believing—30 years of evidence be damned—that today was the day I would open that email, file that invoice, and start that screenplay. Pathologizing my personality felt like a death of possibility. It was almost as if my journey of self-discovery had ended abruptly, not with spiritual transcendence or with confidently alighting towards my purpose but in the DSM-5-TR. I wanted to be more than my brain’s broken reward system.

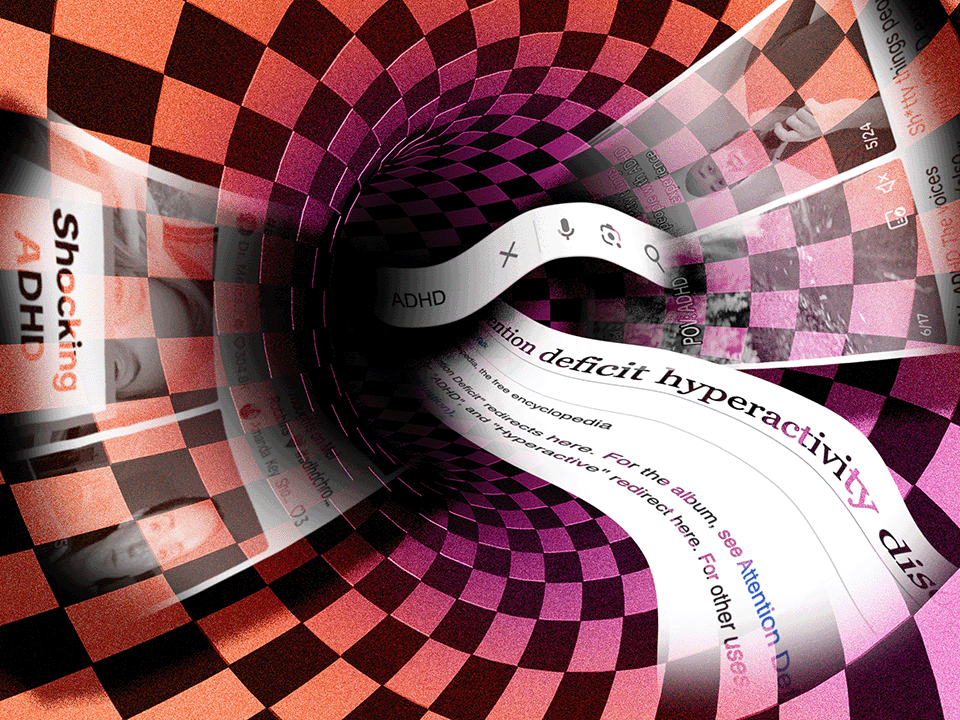

But as I fell into yet another obsessive and time-consuming rabbit hole that would contribute nothing to my goals or finances (duh), the ADHD memes and TikToks started to feel like a breakthrough. This non-stop dopamine-delivery loop of content creators somehow knew exactly how my day was going to play out. The specificity was embarrassing. My horoscope could never. I screenshot every single one and never looked at them again (this is my organizational system).

While it’s true that social media has amplified myths about various symptoms, the ADHD moms on my screen saw me. They, too, had been masking their disorder for decades, working torturously behind the scenes to achieve things that seemed maddeningly easy for everyone else. They helped me identify my deepest fears, like people thinking I’m lazy, or that I don’t actually care about them.

And they helped me see something else: that my unruliness of mind might be the source of almost everything I actually like about myself—openness, curiosity, spontaneity, intuition, and a taste for weirdness. Looking back, ADHD cost me years of sleep, professional opportunities, and too many dollars to count. But I also saw a fundamental restlessness, or impulsivity, or inability to focus on things that are not actually interesting, behind every good decision I’ve ever made.

It’s the reason I moved to New York and sloughed off religion and married a bartender and then burned out and accidentally moved to Australia, where I ate a lot of mushrooms. I wouldn’t take any of this back, even for a lifetime of restful sleep. I am a rule-following, people-pleasing soul who just happens to have a sort of circuitry-level refusal to conform. It’s possible that ADHD has given me a much more interesting life than I ever would have given myself.

A wise editor once told me, as I was having a panic attack in the office (before commuting home, wasting six hours, and then cranking out an overdue assignment between the hours of 12 and 6 a.m.), that this was just my “process.” Back then I thought I could still to-do list my brain into submission. I now know it needs extreme spaciousness like it needs oxygen—to ruminate and investigate and scour Rosalia’s Wikipedia page in a fugue state because it happened to glimpse a headline about Elon Musk, who has children with Grimes, whose song (Oblivion) appears on Pitchfork’s “Best Songs of the 2010s” list with a banger by Rosalia, who seems like an interesting figure I should look into now. My mind craves novelty. This is my cross to bear and my special sauce. No I will not sign that paperwork, not now and probably not ever. But who knows what I’ll do instead?

My diagnosis will not end my logistical and practical struggle to make the most of this one wild and precious life or to stop getting fined by the IRS. But it has given me permission to stop trying to squeeze my mind into a box it won’t fit into, quit screenshotting productivity hacks, and give up asking my brother how to use Evernote.

I now take my meds daily. I pay an app $99 a year to regulate my screen time. I even “body double” with my husband—forcing him to sit next to me on the couch while I open my mail. I cannot stop the internet rabbit holes and I don’t know that I’d want to. It has taken me 40 years to feel less wrong and flawed as a human, and that feels more important.

Now if you’ll excuse me, it’s 3:45 a.m. here in Australia. I need to go to bed.

Wondermind does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Any information published on this website or by this brand is not intended as a replacement for medical advice. Always consult a qualified health or mental health professional with any questions or concerns about your mental health.